Vista Equity Partners has been buying up software used in schools. Parents want to know what the companies do with kids’ data

By: Todd Feathers

Over the past six years, a little-known private equity firm, Vista Equity Partners, has built an educational software empire that wields unseen influence over the educational journeys of tens of millions of children. Along the way, The Markup found, the companies the firm controls have scooped up a massive amount of very personal data on kids, which they use to fuel a suite of predictive analytics products that push the boundaries of technology’s role in education and, in some cases, raise discrimination concerns.

One district we examined uses risk-scoring algorithms from a company in the group, PowerSchool, that incorporate indicators of family wealth to predict a student’s future success—a controversial practice that parents don’t know about—raising troubling questions.

“I did not even realize there was anybody in this space still doing that [using free and reduced lunch status] in a model being used on real kids,” said Ryan Baker, the director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Learning Analytics. “I am surprised and really appalled.”

Vista Equity Partners, which declined to comment for this story, has acquired controlling ownership stakes in some of the leading names in educational technology, including EAB, which sells a suite of college counseling and recruitment products, and PowerSchool, which dominates the market for K-12 data warehousing and analytics. PowerSchool alone claims to hold data on more than 45 million children, including 75 percent of North American K-12 students. Ellucian, a recent Vista acquisition, says it serves 26 million students. And EAB’s products are used by thousands of colleges and universities. But parents of those students say they’ve largely been left in the dark about what data the companies collect and how they use it.

“We are paying these vendors and they are making money on our kids’ data,” said Ellen Zavian, whose son was required to use Naviance, college preparation software recently acquired by PowerSchool, at Montgomery Blair High School in Silver Spring, Md.

After growing concerned about the questions her son was being asked to answer on Naviance-administered surveys, Zavian and other members of a local student privacy group requested access in 2019 to the data the company holds on their children from the district under the Federal Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). But to date, she has received back only usernames and passwords.

“Parents know very little about this process,” she said.

The ed tech companies in Vista’s portfolio appear to operate largely independently, but they have entered into a number of partnerships that deepen the ties of shared ownership. PowerSchool and EAB, for example, have a data integration partnership aimed at “delivering data movement solutions that drive value and save time for Districts.” The two companies also signed another deal last year that made EAB the exclusive reseller of some PowerSchool products.

EAB did not respond to requests for comment.

To piece together the extent of the companies’ data collection, The Markup reviewed thousands of pages of contracts, user manuals, data sharing agreements, and survey questions obtained through public records requests.

We found that the companies, collectively, gather everything from basic demographic information—entered automatically when a student enrolls in school—to data about students’ citizenship status, religious affiliation, school disciplinary records, medical diagnoses, what speed they read and type at, the full text of answers they give on tests, the pictures they draw for assignments, whether they live in a two-parent household, whether they’ve used drugs, been the victim of a crime, or expressed interest in LGBTQ+ groups, among hundreds of other data points. Each Vista-owned company doesn’t necessarily hold all the data points listed here.

Some of those data fields were recorded in the traffic between students’ computers and PowerSchool servers when students used their accounts. The Markup reviewed the accounts with students’ permission. Other data fields were listed in districts’ data privacy agreements with PowerSchool and the data library—a list of all available data fields—for one district’s PowerSchool database. Our review offers a more detailed picture of the company’s data operations than PowerSchool publicly discloses, but it is likely an incomplete portrait.

According to its contracts with school districts, PowerSchool has the right to de-identify the data it holds on their behalf—by removing fields such as names and social security numbers—and use it in any way it sees fit to improve and build its own products.

In some districts, such as Miami-Dade County Public Schools, recent PowerSchool contracts have exceeded $2.5 million for a single year, according to copies of the deals obtained through public records requests.

“It’s hard for me to understand how PowerSchool would not be paying for the privilege” of extracting so much student data, said Alex Bowers, a professor of educational leadership at Columbia University’s Teachers College. “You don’t pay the oil company to come pump oil off your land; it’s the other way around.”

PowerSchool declined to answer specific questions about the data it collects and how it uses that information.

“At PowerSchool, ensuring student equity, privacy, and access to good quality education is our top priority and is foundational to everything we do,” Darron Flagg, the company’s chief compliance and privacy officer, wrote in a brief statement to The Markup. “PowerSchool strictly and proactively follows legal, regulatory, and voluntary requirements for protecting student privacy including the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), state regulations, and the Student Privacy Pledge. PowerSchool customers own their student and school data. We do not sell student or school data; we do not collect, maintain, use, or share student personal information beyond what is authorized by the district, parent, or student.”

A Cautionary Tale: Elgin, Illinois

Many of PowerSchool’s newer product lines, including its predictive analytics tools and personalized learning platform, require troves of student data to train the underlying algorithms. But experts who reviewed The Markup’s findings said that some of the data being used for those purposes is bound to lead to discriminatory outcomes.

Consider School District U-46 in Elgin, Ill., which was the only district—out of 27 we submitted public records requests to—that provided a complete list of the data PowerSchool warehouses on its behalf. The district also provided documents detailing how PowerSchool’s predictive analytics algorithms draw on some of that data to influence students’ educational journeys.

U-46’s PowerSchool database contains nearly 7,000 data fields about Elgin students, parents, and staff, according to a copy of the data library The Markup obtained.

As early as first grade, algorithms from the company’s Unified Insights product line start generating predictions about whether students are at low, moderate, or high risk of not graduating high school on time, not meeting certain standards on the SATs, or not completing two years of college, among other outcomes. The district’s documents describe dozens of different predictive models available via PowerSchool, although U-46 says it does not use most of them.

The district begins displaying student on-time graduation risk scores to teachers and administrators beginning in seventh grade, according to Matt Raimondi, Elgin’s assessment and accountability coordinator.

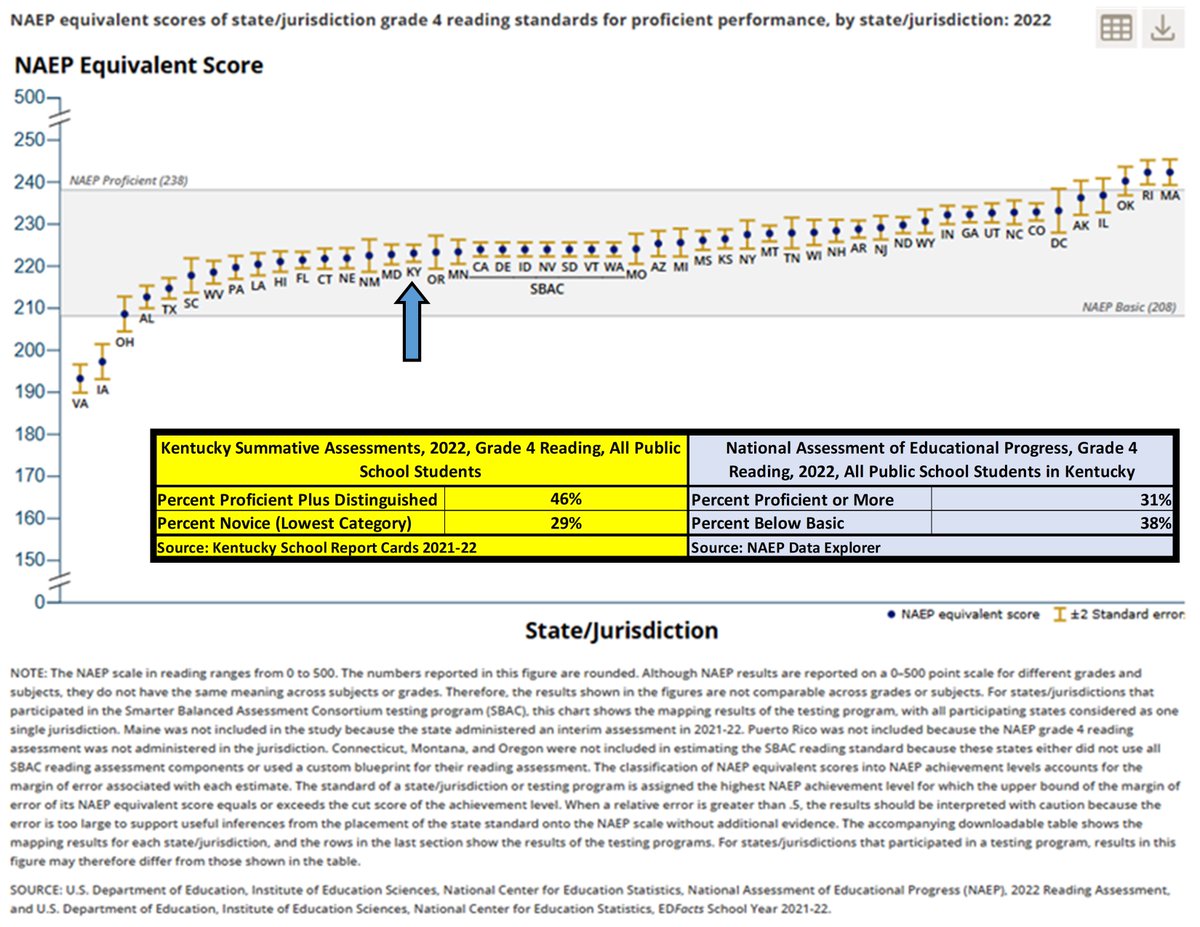

Free and reduced lunch status—a proxy for family wealth—and student gender are among the most important factors in determining that risk score, according to the documents. At one point, Elgin’s models—developed by a company called Hoonuit that was acquired by PowerSchool in 2020 and rebranded as Unified Insights—also incorporated student race as a heavily weighted variable.

Flagg, from PowerSchool, said race was removed from the models in 2017 before the company acquired Hoonuit.

The predictive models also draw on data points like attendance, disciplinary history, and test scores.

Learning analytics experts told The Markup that the use of demographic data like gender and free and reduced lunch status—attributes that students and school officials can’t change—to predict student outcomes is bound to encode discrimination into the predictive models.

“I think that having [free and reduced lunch status] as a predictor in the model is indefensible in 2021,” said Baker of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Learning Analytics. Baker has consulted with BrightBytes, a competitor of PowerSchool in the K-12 predictive analytics space.

“Unified Insights does provide the option for school districts to include free and reduced lunch status to enable districts to reduce dropout risk associated with economic hardship and identify additional social service supports that may be available to impacted students,” Flagg, from PowerSchool, wrote in an email.

“Including these things that are not within the control of the family or the school is highly problematic,” said Bowers, from Columbia University Teachers College, because even the best-intentioned school cannot change all the systemic gender and wealth disparities that affect a particular student. Basing the risk scores so heavily on those factors therefore obscures the impact of other factors a school may be able to influence, he said.

Raimondi said U-46 has chosen not to use many of the predictive models PowerSchool makes available because of their reliance on immutable student characteristics

“Especially down at the early grades, we don’t even make it visible to any users besides myself and a programmer,” he said. “The models at the lower grades, they’re not that accurate and they rely a lot more heavily on demographic-type data.”

Each year, Elgin’s dropout risk model misses about 90 students in each grade level, out of 3,000 students per grade, who do not go on to graduate on time, according to a presentation prepared by a PowerSchool data scientist and obtained by The Markup.

“We have no comment on the sensitivity/specificity of the models,” U-46 spokesperson Karla Jiménez wrote in an email.

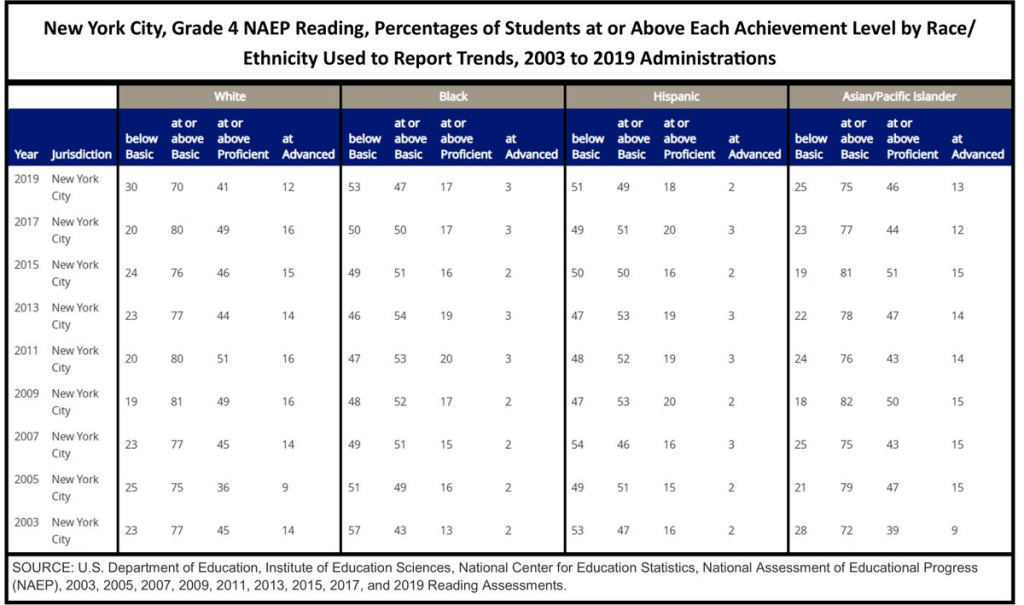

The Markup has previously reported on a similar dropout prediction tool EAB sells to colleges and universities. Some of those schools incorporated race as a “high impact predictor” of success, and their algorithms labeled Black students “high risk” at as much as four times the rate of their White peers, effectively steering students of color away from certain majors. After our reporting, Texas A&M University dropped the use of race as a predictive variable.

The Data Empire Is Growing

Vista Equity Partners has been expanding its reach in the educational software industry for years. Along with that expansion, it’s put together a portfolio of companies that amass data and effectively track kids throughout their educational journeys.

Since 2015, when Vista first purchased PowerSchool from Pearson for $350 million, Vista has been on a spending spree, acquiring other ed tech companies that collect different kinds of student data.

In 2017, PowerSchool bought SunGard K-12, which provided human resources and payroll software for schools. In 2019, it purchased Schoology, a widely used learning management system that served as the digital backbone for many schools’ curriculum and lesson plans. It acquired Hoonuit, which provides the predictive risk scoring used by districts like Elgin, in 2020.

Last March, it completed the purchase of the college preparatory software Naviance, and in November it purchased Kickboard, a company that collects data about students’ behavior and social-emotional skills. In presentations to investors, PowerSchool officials have said more acquisitions are a key part of the company’s growth plan.

EAB has been on a similar purchasing spree, acquiring companies like Wisr, YouVisit, Cappex, and Starfish that are used for college recruitment, advertising, and tracking students on campus. It also announced the creation of Edify, a “next-generation data warehouse and analytics hub” designed to “break down data silos.”

Last June, Vista also acquired a co-ownership stake in Ellucian, which sells a variety of educational technology products. The company claims to serve more than 26 million students across 2,700 institutions.

That consolidation of data and power has triggered a backlash from privacy-minded parents, some of whom have been trying, unsuccessfully, to find out what the deals mean for their children’s sensitive data.

Piercing the veil of secrecy can be difficult, even when parents turn to privacy laws designed to increase transparency.

Illinois, for example, has a state law that requires school districts to post specific information about the ed tech vendors they use, including all written agreements with vendors and lists of the data elements shared with those vendors.

Despite that, districts like Chicago Public Schools have yet to post any of the required material pertaining to PowerSchool and Naviance. CPS has, however, posted data use disclosures for other vendors. Across Illinois, 5,800 schools use PowerSchool software, according to the company.

FERPA has also proven of little use for some parents.

Cheri Kiesecker, a Colorado parent of two, said that she requested her children’s records under the law from PowerSchool earlier this year after it completed the Naviance deal.

“Each school district owns and controls access to its students’ data, Flagg, from PowerSchool, wrote in an email to The Markup. “Any requests from parents for access to their children’s data must be managed through their respective school districts.

PowerSchool instructed Kiesecker to request the records through the school, which she did. When PowerSchool did not comply with the school’s subsequent request by the statutory 45-day deadline, her school’s attorneys sent a legal demand to the company, which The Markup reviewed. To date, Kiesecker said, she has still not received her children’s complete records, although PowerSchool has provided partial documentation.

Deborah Simmons, a Texas parent, said she began looking into the Vista-owned companies after discovering that her school had automatically uploaded her child’s data into Naviance. She filed public records requests and grievances with her school but still doesn’t know the full extent of the data the companies hold or who else it’s been shared with.

“These tech companies want to eliminate the data silos and merge and streamline all of this stuff, but no, our children aren’t products,” Simmons said. That’s what they do, they treat our children like products. They’re human beings and they deserve privacy and freedom.”

This article was originally published on The Markup and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

Agustin Tristan

Agustin Tristan American Psychological Association

American Psychological Association Brain Health Alliance Virtual Institute (BHAVI)

Brain Health Alliance Virtual Institute (BHAVI) Catherine & Katharine

Catherine & Katharine Critically Speaking

Critically Speaking Education Consumers Foundation

Education Consumers Foundation Facilitated Communication Blog

Facilitated Communication Blog Fulcrum, The

Fulcrum, The Institute for Objective Policy Assessment

Institute for Objective Policy Assessment James G Martin Center for Academic Renewal

James G Martin Center for Academic Renewal Learning Scientists

Learning Scientists National Association of Scholars

National Association of Scholars Nonpartisan Education Review

Nonpartisan Education Review Represent Us

Represent Us Retraction Watch

Retraction Watch